The Children Behind the Diagnosis: Insights from Siyakwazi’s First ASD Block Week of 2025

In April 2025, Siyakwazi held its first Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Block Week of the year – a foundational intervention that takes place twice annually as part of the organisation’s ongoing work with children with disabilities in rural KwaZulu-Natal. Designed as both an intensive support programme and a practical onboarding process, the Block Week introduces newly enrolled families to the principles of inclusive learning, therapy-informed care, and what it means to raise and support a child with ASD where services are sparse and stigma remains high.

This year’s first Block Week welcomed six children and their caregivers. While their circumstances varied, their stories revealed a common thread: families were navigating their children’s diagnoses with very limited guidance, often facing isolation, confusion, and uncertainty about what to do next.

Four-year-old *Njabulo is enrolled at a local ECD centre and was recently diagnosed with ASD. Before attending the Block Week, his mother believed he simply had delayed speech. It wasn’t until later that she began to understand the complexity of his needs. Njabulo can smile and play independently, but is not yet toilet trained and struggles to communicate. His mother’s biggest concern is whether his teachers understand him and know how to manage his behaviour. “There are moments where I see him do things on his own and it brings me joy,” she shared, “but I’m often just cleaning up after him, and it’s exhausting.”

*Ayanda, aged seven, is non-verbal and highly active. She feeds and dresses herself independently, but cannot speak or follow instructions. Her mother came into the Block Week seeking practical answers: “I wanted to see how therapists calm her and teach her – how I can do it too.” She also hoped to learn how to access a school that could accommodate Ayanda’s needs, having been turned away from multiple mainstream options.

For *Buyisiwe, age five, schooling is already a struggle. While enrolled in a primary school, he is not able to participate in lessons, is frequently agitated, and shows signs of cognitive and communication delays. His mother admitted to stopping his medication out of denial. “At home they said it was my fault,” she said. “I didn’t believe the doctors when they said it was autism. Now I can see it clearly.” For her, the Block Week became a turning point – an opportunity to re-engage with support and make informed decisions about his care.

Four-year-old *Ndumiso is not enrolled in any learning setting and had never received any therapy before joining Siyakwazi. He is still in nappies, cannot communicate verbally, and struggles to interact with other children. “We accept him at home,” his mother said, “but I worry about whether other children will include him or tease him.” For this family, the Block Week was a first exposure to developmental information, structured support, and long-term planning for their child.

*Nolwazi, age five, has a broad range of barriers including limited speech, difficulty with concentration, and physical weakness. His mother described her heartbreak after receiving the diagnosis but also the renewed hope she felt during the week. “He enjoys learning, especially using sticks like DJ equipment,” she said. “Before, I didn’t know how to help him. Now I do.” The Block Week gave her clarity on how to handle meltdowns and how to structure his day in a way that meets his needs.

Finally, *Lindo, a five-year-old with suspected ASD, is not yet formally diagnosed. His mother noted that while he doesn’t show severe developmental delays, his speech is unclear and he struggles to express himself. She had previously dismissed concerns, thinking he was simply shy. “But now I’m not so sure,” she said. “Maybe he needs help too.” For caregivers like her, the Block Week provides a vital space for early identification and onward referral.

Understanding, not just awareness

A central theme emerging from the week was the gap between awareness and understanding. Most caregivers had heard of ASD, but few had accurate information about what it meant. Some believed it was caused by stress during pregnancy or thought it was an untreatable illness that made children “not normal”. Others assumed it was a phase their child would grow out of.

But as the week unfolded, caregivers’ attitudes began to shift. They learned about sensory processing, communication alternatives, how to manage behavioural challenges, and the importance of structure and routine. In group discussions, they compared notes on feeding difficulties and shared practical strategies – like how to make vegetables more appealing or how to support non-verbal children using song and gestures.

The Block Week also allowed space for emotional processing. Parents spoke honestly about their fears: being excluded from school, being judged by neighbours, or being blamed by extended family. They shared how hard it had been to accept the diagnosis, but also how reassuring it was to realise they weren’t alone.

Measurable shifts

Before and after the Block Week, caregivers completed reflection questionnaires. At the beginning, most described their role as simply “supporting” or “loving” their child. By the end, they were identifying specific support needs – speech therapy, sensory-friendly environments, specialised schools – and seeing their role as more proactive and informed.

Caregivers also described more meaningful engagement at home. They plan to begin doing structured play, encouraging daily routines, and creating calm-down spaces. One mother said she would start playing educational games with her child, instead of just watching educational kids’ TV together, realising that active engagement could help her child learn and connect better. Another planned to revisit the hospital to re-initiate her child’s therapy that she had previously declined.

The role of the Block Week

Siyakwazi’s ASD Block Weeks serve as both a training platform and a launchpad. For newly enrolled families, it’s often the first time they’ve had focused attention, access to specialists, and the opportunity to see their child through a different lens. It is the start of a longer journey – one that includes home visits, therapy access, inclusive education advocacy, and peer support.

But the week also highlighted systemic issues: poor access to diagnosis, unclear referral pathways, and limited school readiness for children with ASD. Families were asking: Where can my child go to school? Who will understand them? What happens when the therapy ends?

What comes next

The Block Week is not a one-off event – it’s the beginning of a longer-term relationship between families, children, and the systems that must support them. Siyakwazi’s work continues beyond these five days, through regular home visits, coordination with schools and clinics, and by strengthening referrals to health and social services.

But no single organisation can meet this need alone. The challenges faced by families – delayed diagnoses, a lack of inclusive schooling options, and limited access to therapy – are systemic. They require coordinated action across government departments, local service providers, and community-based organisations.

For funders and partners, Block Week offers a replicable and meaningful entry point. It provides a way to reach families early and begin building the kind of consistent, structured support that children with ASD need to thrive. The families who participated in this Block Week have taken the first step. What’s needed now is sustained, scalable investment in systems that continue to support them – through every stage of their child’s development.

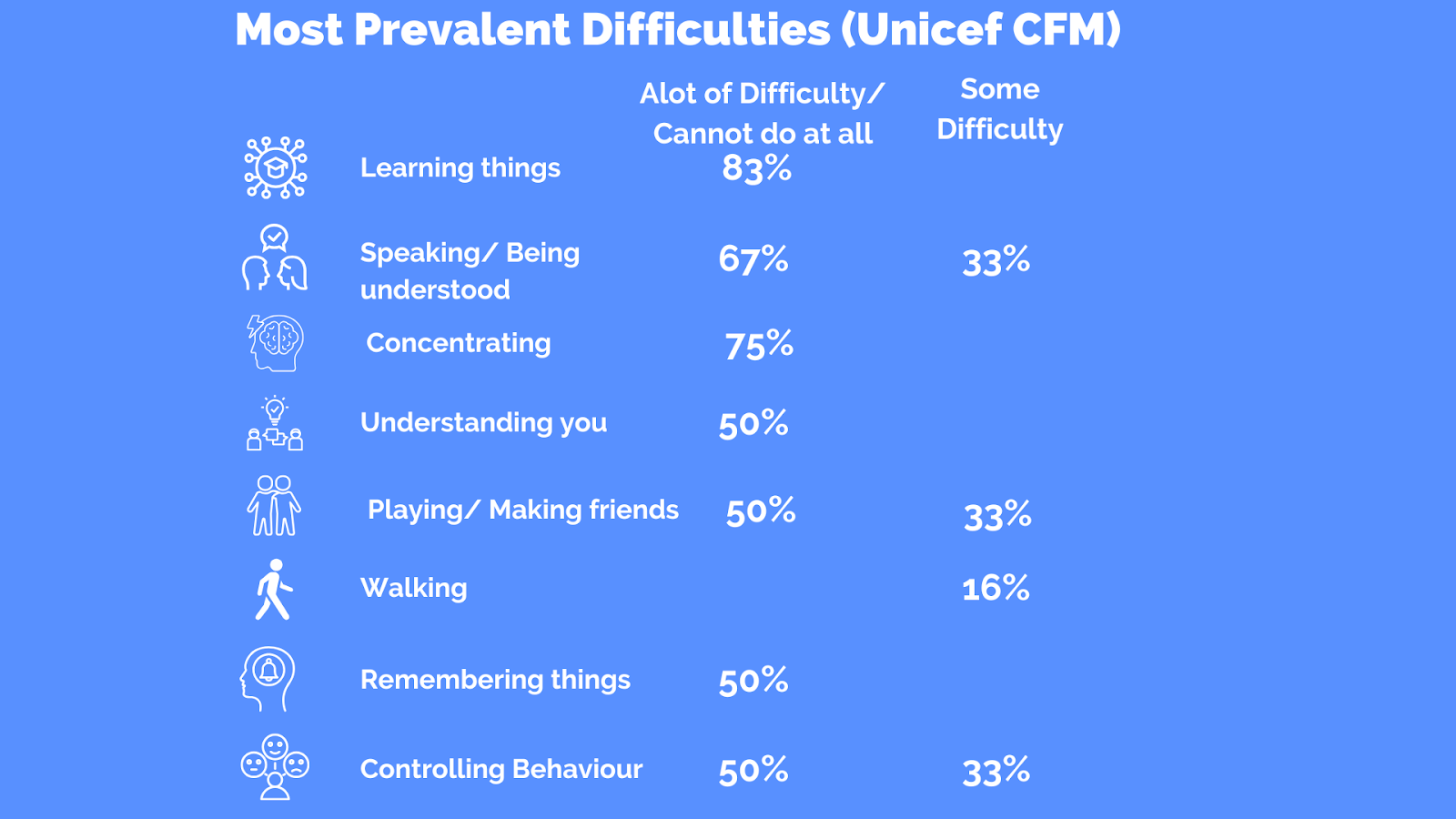

NOTE: The Child Functioning Model (CFM) is a framework developed by UNICEF to assess how children function in daily life across key developmental domains, such as seeing, hearing, mobility, communication, learning, and behaviour. It helps identify children with functional difficulties to ensure they receive appropriate support and inclusive services.

*Names changed for safeguarding and privacy.